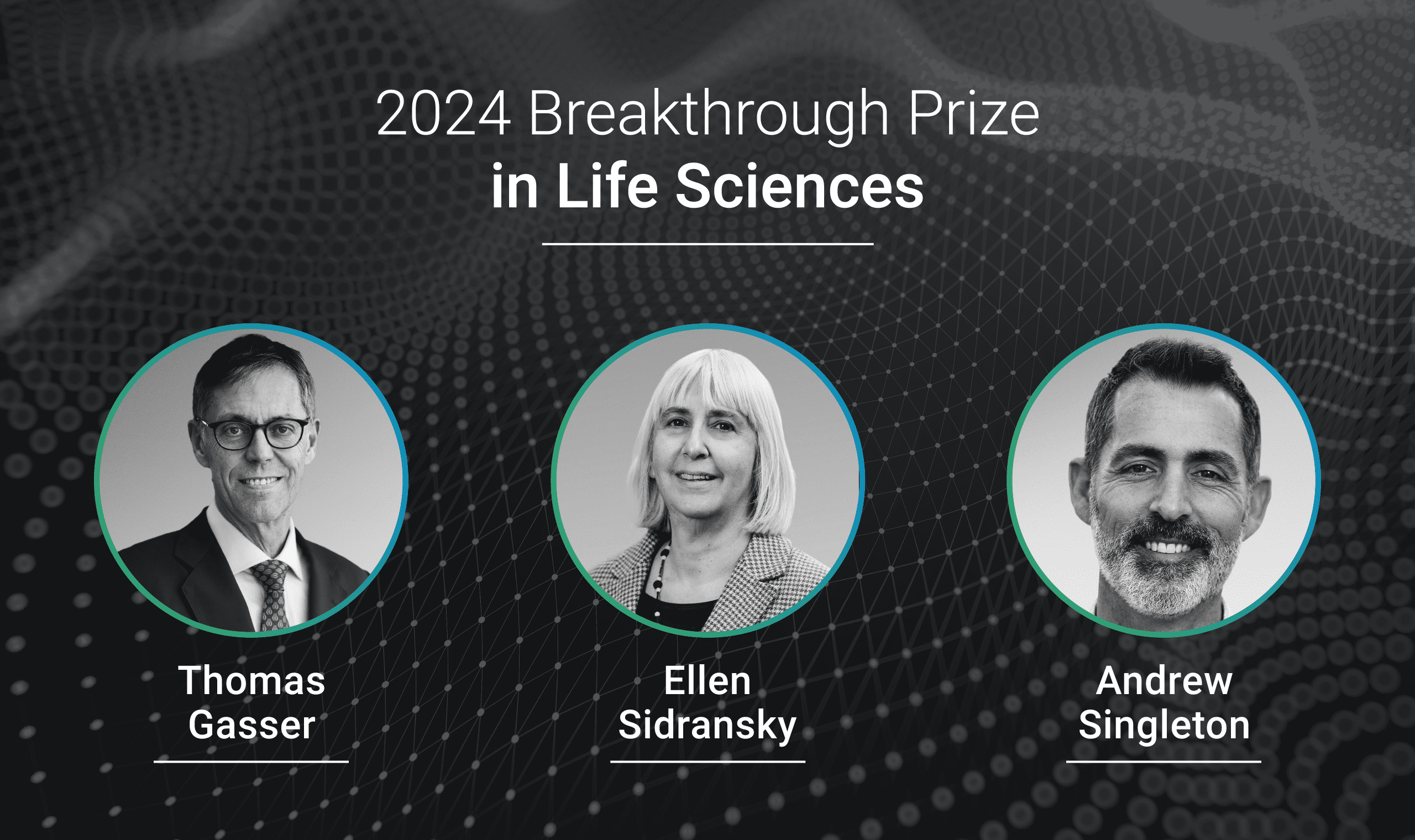

Breakthrough Prizes 2024 – Interview with Andy Singleton, Thomas Gasser, and Ellen Sidransky

Last September 14th, the Breakthrough Prize Foundation announced Andrew Singleton, Thomas Gasser, and Ellen Sidransky as the three recipients of the 2024 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences. Known as the “Oscars of Science,” the Breakthrough Prizes “honor the world’s most brilliant minds for impactful scientific discoveries.”

Can you tell us about your background? How did you find your way into Parkinson’s/ADRD/dementia genetics research?

Andy: I was born and raised on a small island called Guernsey. After an unsuccessful year working as an accountant, I went to Sunderland University to study Applied Physiology. During that time, I got to experience working in a lab for a year, primarily on the genetics of dementia. I came back to that lab to complete a PhD, again on the genetics of Alzheimer’s and Lewy body dementia. Then I moved to the U.S., where I worked for John Hardy at the Mayo Clinic, investigating Parkinson’s disease.

Tom: When I studied medicine, I was certain early on that I also wanted to do research. I first spent some time as a student in pharmacology researching anti-cancer drugs, but during my clinical training, I became more interested in neurology and neuroscience. It was then, just by chance, that I found my first position as a neurology resident in Munich in the group of Wolfgang Oertel, who was working on Parkinson’s disease.

Ellen: I was introduced to research at an early age, as my father was an academic pathologist. In college, I deliberated between a PhD track and Medical School, but really fell in love with the clinical aspects of medicine during my different rotations in med school. I chose to do Pediatrics, but always found time to do research projects. Ultimately I came to NIH to receive training in Medical Genetics. I began working in the laboratory of Edward Ginns, who had just cloned the glucocerebrosidase gene. I started by studying diverse patients with Gaucher disease, striving to identify the molecular causes of the associated clinical heterogeneity. Among the patients that I evaluated was one with both Gaucher disease and parkinsonism. That opened up the field for me, and the rest is history. As a pediatrician, I never dreamed that my career would focus on Parkinson’s disease.

What is the biggest change you’ve observed in our understanding/conceptualization of Parkinson’s over your career? How has your own understanding or thinking about this disease changed over time?

Andy: I think there are so many challenges. I’m particularly interested in understanding the basis of the variance we see in Parkinson’s disease – Why do patients progress so differently?

Tom: When I started, it was all about dopamine deficiency and how to replace this neurotransmitter. Today, we know that dopamine deficiency is pretty far downstream of many diverse pathologic processes, and we are much more interested in those because they will lead the way to true causative treatments.

Ellen: A lot more is known now about the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease, but there is still a long road ahead. I am delighted that our genetic advances have directed attention to the role of the lysosome and have introduced new therapeutic targets for further development. From my more Gaucher-centric approach, I am focusing attention on why only a vast minority of patients with Gaucher disease or GBA1 mutation carriers develop Parkinson’s disease. There must be other important factors that confer additional risk or protection.

You’ve earned the Breakthrough Prize for the discovery of key genes related to Parkinson’s disease. What does this prize mean to you personally? How did you feel when you found out you earned it?

Andy: I don’t think it seemed real for a long time… but of course, very, very happy! I think that, like my colleagues, I don’t really enjoy attention, and find it a little overwhelming sometimes… but again, that’s a good problem to have!

Tom: Like Andy, of course very happy! I also realize that over the years, many researchers have picked up on Parkinson’s disease genetics and have done wonderful work. I feel like the prize is a recognition for the entire field.

Ellen: I was stunned to hear that I was selected for the prize. As someone who spent my entire career working on a rare disease, a prize like this seemed inconceivable. Also, early on, I struggled to get the beginning of the glucocerebrosidase story published. I am gratified that this recognition supports the value of studying rare disorders. Patients with rare disorders need our support. The disorders teach us a lot about basic biology, and as in this case, they can provide unique insights into more common diseases.

Can you tell us more about the key gene/s and related gene variants whose discovery earned you the Breakthrough Prize? What is your favorite fun fact about this/these genes and variants, or what is something that you wish more people knew about?

Andy: Essentially, this is a recognition for the discovery of LRRK2 mutations as a cause of Parkinson’s disease, and for follow-on work showing that the p.G2019S mutation is remarkably common. My favorite fact is that the “transcript” that we were essentially sequencing was called “DKFZp434H2111” – hard to forget that name…

Tom: When we identified mutations in several families, we looked for gene expression in the brain, and it turned out that expression in substantia nigra was uncomfortably low. We had a lot of doubts that this was really the right gene until we finally heard that Andy and his team had identified the same gene.

Ellen: I’ve been focused on my gene, GBA1, for more than three decades. It has a very analogous copy called a pseudogene located very close by. This extra sequence complicates genomic analysis in this region on chromosome 1. Many times, researchers have confused variants in the two sequences.

Is there a particularly vivid memory that stands out to you related to your work on the key genes that earned the 2024 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences? Can you tell us about a key moment?

Andy: I can remember many moments, including the phone call where Nick Wood, Jordi Perez Tur, Jose Felix Marti-Masso, and I decided to join forces to hunt for the mutation. The excitement of working with two incredible graduate students, Coro Paisan-Ruiz and Shushant Jain, and of them sharing sequencing results across the Atlantic in the mornings and evenings. Figuring out that the Basque families were distantly related, which narrowed the critical interval that we were looking in by a huge amount. Chatting with Mark Cookson and John Hardy about the potential function… lots of good memories.

Tom: I vividly remember that when we were chasing the gene in a family that Zig Wszolek had identified in Nebraska, we almost abandoned the project when it turned out that some affected members from this family who had come to autopsy, actually had different pathologies, some with Lewy bodies, some without. So we were afraid that although coming from one family, those individuals might not have the same disease. In fact, they have the same disease genetically but with different pathologies, still an unsolved conundrum.

Ellen: After I published a series of 18 patients with both Gaucher disease and parkinsonism, I received a call from a former student, Kathy Newell, who was then the chief neuropathology fellow at MGM. She was doing an autopsy on a patient with Parkinson’s disease and read in the chart that he also had Gaucher disease. She wondered if I wanted samples from the autopsy. I certainly did, but also asked her for a few other samples with Parkinson’s disease. Three samples arrived on dry ice, but we could not read the labels. So we measured glucocerebrosidase activity and extracted DNA and determined that the two Parkinson’s ”controls” carried GBA1 mutations! This was the aha moment!

Where do you see the field and research efforts in Parkinson’s genetics going in the future?

Andy: I think the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2) is a large part of that future. Diversifying our efforts by including patients and researchers from around the world is critical. GP2 also supports skilled researchers and gives them opportunities for growth. GP2 is really a culmination of experience over the last 20 years. It’s about understanding that if you can work with a great group of motivated researchers, you can make a substantial difference.

Tom: We are now conducting the first promising treatment trials in genetically stratified Parkinson’s disease patients, which is really based on our genetic discoveries: for me as a neurologist who still sees many Parkinson’s disease patients, this is very exciting!

Ellen: Genetics research is leading to the recognition of new pathways involved in Parkinson’s pathogenesis. These provide new targets for therapeutic development, which may accelerate drug development.

How have collaboration and teamwork been instrumental to your work and discoveries?

Andy: In every way. Now, genetics is completely collaborative and all we do is “team science.” It’s remarkably challenging and rewarding!

Tom: In contrast to when we began working on families with Parkinson’s disease, genetics is now a highly collaborative effort, maybe more so than most other areas of biomedical research.

Ellen: Collaboration is absolutely essential in genetics. The international collaborative study on GBA1 mutations in Parkinson’s disease in the NEJM was essentially what led to widespread acceptance of the finding. Now that we are searching for genetic modifiers, we need to combine forces to attain the power to identify additional factors influencing disease penetrance.

What are some current findings, technologies, tools, or ideas you are particularly excited or hopeful about related to the field of Parkinson’s genetics and our understanding of these diseases?

Andy: Long-read sequencing is pretty exciting, particularly with the overlay of methylation for DNA. Additionally, its application for transcriptomics and more distantly for proteomics is really exciting.

Tom: When I got into neurology, a common way of thinking was that neurologists were pretty smart about diagnosing a large number of diseases that they could do absolutely nothing about. This has changed dramatically, and genetics has played an enormous role in this tradition, particularly in neurodegenerative diseases.

Ellen: We have focused on iPSC-derived models, high throughput sequencing, and multi-omic approaches to better understand the biology and to identify new drugs.

What has been the biggest challenge you’ve had to overcome to achieve success in this field?

Andy: It’s essential that you meet colleagues and make connections. I’m very introverted. I find it hard to meet and talk with people, and sometimes hard to get up and speak in front of others. I have to work on this all of the time.

Tom: The biggest challenge for me has been balancing everyday clinical practice and the long-term research effort. Many talented colleagues need help finding this balance, and you can only do it in a good team.

Ellen: I also find balancing clinical responsibilities and managing a lab challenging. It was also challenging to enter an entirely new field – neurodegeneration – later in my career.

What advice do you have for other researchers in this field?

Andy: Work with people you like.

Tom: …and be persistent, even when progress is slow!

Ellen: Cherish your exceptions – they are telling us something important. And don’t be afraid to get it wrong.

How do you maintain your own life balance and hope for the future as a researcher in this field?

Andy: I think you have to prioritize a home life… there are certainly times when you have to work like crazy, but in general, you need to be a little selfish about time at home. I don’t really remember working in the lab writing a paper, but I do remember sitting around having dinner with my family or reading to my kids.

Tom: Yet another extremely important balance! Family life is of course at the heart of it, but other things like playing music, Jazz saxophone in my case, can also help a lot.

Ellen: For me, this was really necessary as we raised four children. Some years were very difficult. But I learned so much from parenting, especially about individual differences and different ways of learning. And just when I thought I’d have more time, then came the grandchildren – they are the best reward!

What would you like to see in your lifetime in relation to PD or what is the biggest remaining challenge?

Andy: Prediction and treatment tied together, so that patients are treated before they even know they’re ill.

Tom: Indeed, the relationship between genetic dispositions and risk and actually becoming sick is extremely complex. We may have to focus more on factors of resilience – they have been largely ignored so far.

Ellen: Presymptomatic treatment would be awesome. But so would any therapy that would substantially alter the disease trajectory.

Congratulations to Thomas Gasser, Ellen Sidransky, and Andrew Singleton, who won the 2024 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for discovering key genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s disease.

Thomas Gasser, Ellen Sidransky, Andrew Singleton: 2024 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences