Despite growing up and starting my scientific career in Spain, before the first human genome was even sequenced, it never crossed my mind that research is extremely Euro-centric (solely focused in populations of European ancestry). Even when I moved to Florida in 2004, a state where Latinos are largely represented, and I was working only with samples from participants mostly from European descent, I still never questioned the reason behind it.

However in 2006, a trip to the land of the Incas, Peru, where I spoke at a conference organized by the Latin American Society of Movement Disorders, opened my eyes to the lack of Latino representation in the field. Movement disorders specialists from almost every country in Latin America listened to me talking about the genetics of Parkinson’s disease (PD), and this new gene called LRRK2 which seemed to cause PD in 1-2% of patients. During my Q&A many clinicians asked me if I knew how frequent mutations in this gene were in Latinos and how they could get all their patients tested. Right there, in front of all of them I had to admit that the field did not know. All the studies had been done in individuals of European ancestry.

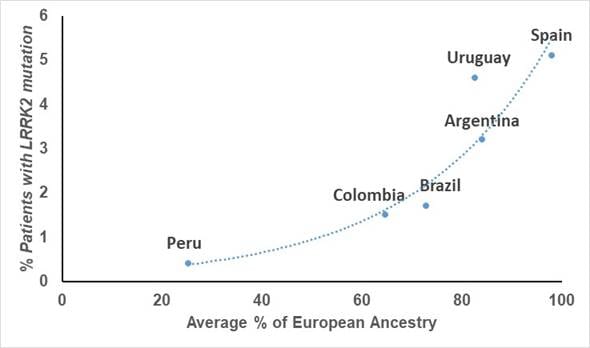

Although Latinos do have some European ancestry, this is highly variable in each person, even within the same country. In fact, fast-forwarding a few years, studies done on the patients of these same clinicians showed that the frequency of mutations in LRRK2 is highly linked to the amount of European ancestry that each country has on average, with countries like Peru that has the least amount of European genetic material, having the lowest frequency.

Graph showing the relationship between frequency of LRRK2 mutations and amount of European ancestry in each country (From Zabetian et al. 2017)

Studies in another PD gene, GBA, have shown that not only the frequency, but also the type of mutation that you can find in each Latin American country, are different, and sometimes population-specific.

All of these findings have important repercussions when trying to decide, for example, what genes to test for in a certain population or for selecting what therapeutic targets would be most important in each patient cohort. As we know more about the role of genetics in PD, this information will be crucial to predict who is at high risk to develop this (or any other) disease, as well as the many different outcomes that can be influenced by genetics.

And while I talked here about Latinos, this is also applicable to many other large underrepresented populations, such as those from Africa, India or South East Asia. This is a tremendous problem we must resolve, especially as we head towards precision/personalized medicine, as this lack of knowledge will increase the already existing health disparities.

The good news is that there is more awareness about this issue, which has fueled the creation of worldwide efforts to repair this. The Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson’s Genetic Program (GP2) is bringing researchers together from around the globe to further understand the genetic architecture of PD, with a specific focus on those underrepresented populations. The goal is to study at least 150K new volunteers, including 50K non-European individuals coming from Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, India, South East Asia, China, and minority populations from the US.

I am hopeful that, through our global collaboration, we will make tremendous strides towards increasing diversity in genetic studies and minimizing health disparities in underrepresented populations. I encourage you to join this effort.

With thanks to Emily Mason, a new member of the Mata lab, for her support in writing this blog post.